Ruck Marching – Every Day is “Hump Day”

I’ve been carrying a rucksack for more than 20 years and confident I’ve put hundreds, maybe thousands, of miles on my feet with a ruck on my back.

Most people that have experienced life under a ruck often say it’s more mental than physical. I agree with that statement 100% and add that the toughest six inches of any road march is directly between your ears.

I took an interest in ruck marching because at the beginning I struggled and often found myself falling to the rear of the pack. I have come a long way since those days in the early nineties.

Recently, one of our defenders returned from the Air Force Combat Leaders Course (CLC) and described the ruck standards; to which several defenders became concerned they wouldn’t be able to meet. I decided to put together some information to help them along.

If you’ve been out of the game for a while, or you’re just starting out, I think this information, along with the 12-week plan below, can help you prepare for an upcoming school, deployment, or if you’re simply looking at burning serious calories while building your endurance under a rucksack.

Why would someone want to follow a specific program for something that seems as simple as walking? It is necessary for adaptation. Your bones, connective tissue, and muscles need to get accustomed to carrying heavy loads on your back and for long distances. If you fail to follow a program that gradually introduces your body to the type of movements and mechanics of rucking; the body may not adapt properly and problems occur. But if you follow a solid program, you can avoid that fate.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Make sure your kit fits and that you are wearing it properly. This includes weight distribution in your ruck. The majority of your ruck’s weight should rest on your hips, not your shoulders. The shoulder straps are there to merely keep the ruck from falling backwards.

- Do two marches per week — a slow march and a fast march — separated by two to three days. As you increase in distance, you may want to consider using a Saturday or Sunday so you’re not pressed for time before or after work.

- Your pace for the slow march should allow you to hold a steady conversation through the march.

- During your fast march, the pace should limit you to speaking in quick bursts, and you should be just out of breath the entire time. You should not be marching as fast as you can — you have to build load-bearing capacity first.

- Make sure you’re getting plenty of sleep and eating plenty of carbohydrates. No creatine or protein powder — just lots of organic carbs and water. If you don’t start hydrating until you step off for your march, you’re setting yourself up for failure. As one of my mentors explained almost two decades ago; “today’s water is for tomorrow.”

- Do not wear cushioned boots — cushion causes joint instability and will cause severe micro-trauma and fatigue. DO NOT WEAR ATHLETIC SHOES!

- Do not alter the body weight percentages outlined in the accompanying plan. Stick to the plan!

- Do not exceed 30% of your body weight in an effort to improve your endurance, ever. Upon completing this plan, limit your rucking to a maximum of four per month, with at least one of them being 30% body weight for nine miles to help maintain your conditioning.

- Never run with a ruck! If the time comes where your life or your mission requires you to run with a ruck, then run with a ruck; but don’t train by running with a ruck or your body will pay the price later in life. However, in the process of your training YOU WILL BE SORE. Learn the difference between soreness and injury. If you are injured (a blister is not an injury), heal, then work your way back into it. Being injured doesn’t do you, your unit, or the mission any good.

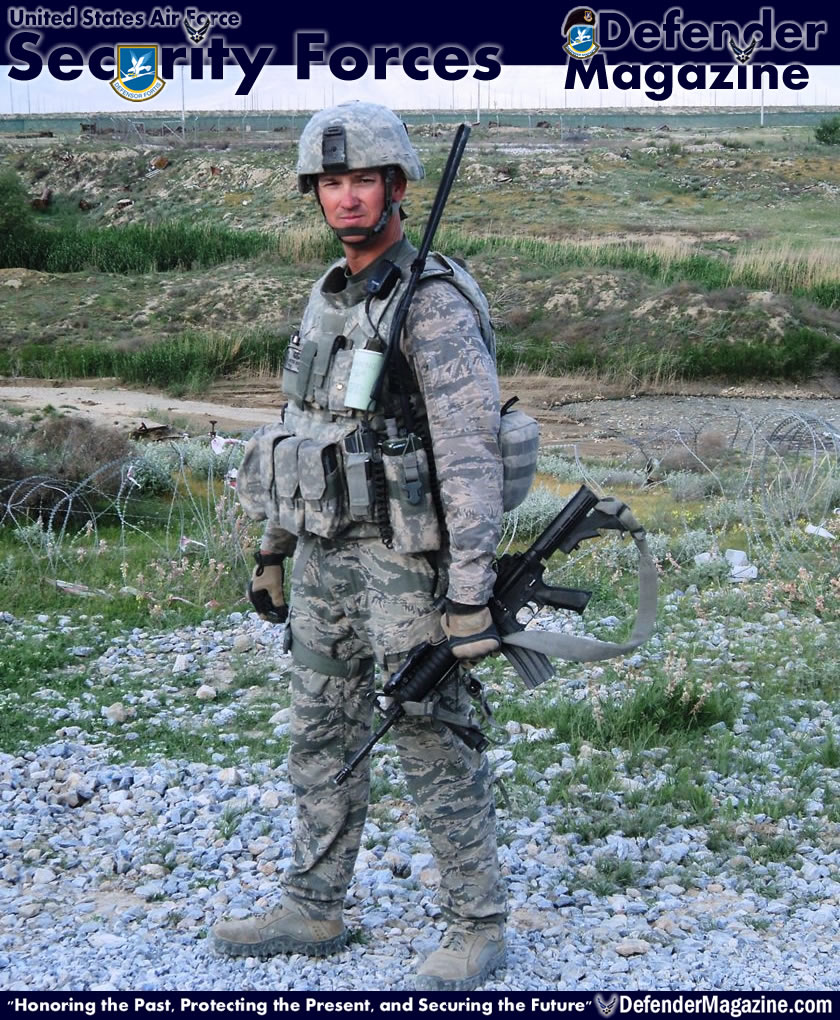

- While wearing shorts and athletic clothes may be more comfortable, if you are training for a school such as CLC, Ranger, or Air Assault, then practice your rucking while wearing the same uniform you’ll wear at the school or while on a real-world op.

Don’t be late. Don’t be light. Don’t be last! Throughout the military there are several schools where ruck marches are a part of the evaluation of students and can determine whether or not you meet the standards. During these schools, your ruck will be weighed before, during, and after each march. If you are light, you will fail that progress check. Combat Leaders Course, Ranger and Air Assault schools all share this standard. And be advised, that your weapon, ammunition and water don’t count as weight.

Here is a proven plan that will take you through 12 weeks of twice-a-week ruck marches. It includes a percentage of your body weight, distance, and relative pace.

Week 1: 15% + 3 miles Slow/fast

Week 2: 15% + 3 miles Fast/slow

Week 3: 20% + 5 miles Slow/fast

Week 4: 20% + 5 miles Fast/slow

Week 5: 25% + 5 miles Slow/fast

Week 6: 25% + 5 miles Fast/slow

Week 7: 30% + 5 miles Slow/fast

Week 8: 30% + 5 miles Fast/slow

Week 9: 30% + 7 miles Slow/fast

Week 10: 30% + 7 miles Fast/slow

Week 11: 30% + 9 miles Slow/fast

Week 12: 30% + 9 miles Slow/fast

Weight example: If you weigh 200 lbs., your ruck would weigh 60 lbs. (30% of your body weight). Add six quarts of water at 2 lbs. per quart, and your ruck now weighs 72 lbs. You should understand that the load you carry in combat – on real world missions, will NOT be based on a percentage of your body weight. Whether you are 5’ 2” and 115 lbs., or 6’ 4” and 250 lbs., your load will be equal to that of everyone else and be relevant to mission requirements. The standard combat load for a deployed defender performing air base defense is roughly 50 lbs., and this does not include any type of pack.

Note: The US Air Force Security Forces standard for graded ruck marches at the Combat Leaders Course is 30% of your body weight (plus 6 quarts of water) for 9 miles in less than 150 minutes; a 16:40 minute per mile pace.

Tips and Tricks of the Trade

Veteran ground fighters from all branches who have been required to ruck march as part of a unit or mission requirement, or even as part of a course curriculum, may suggest a variety of advice on how to survive long marches with the burden of heavy weight on your back.

Here, I’ll list a handful of suggestions I’ve heard over the years that people swear on making an endurance march more tolerable. Use at your own risk…

- Sock liners can alleviate hot spots and blisters. Many people suggest using woman’s nylons, but there are commercial options available designed specifically for this; such as Fox River Military boot socks available at AAFES or outdoor stores like REI, Dick’s or Academy

- Use the waist strap of the pack. Although many infantrymen remove the pack’s belt, or tape it back, on long marches (not combat patrols where you may need to “quick release), this can save your shoulders

- Powder your feet! Foot powder will keep your feet dry and reduce the friction between your foot and your boot

- Don’t wear boxer shorts. If you’ve never seen a man rip their underwear off without removing their pants; while on the move, then suggest they wear boxers on a ruck march and you’ll be impressed

- Chaffing happens and it can cause a lot of discomfort. There are commercial anti-chafe products like Body Glide available, but try it out before you start rubbing it all over on a long distance march

- Carry moleskin. If you aren’t familiar with moleskin, buy some and carry it with you. You’ll figure it out when the time comes

- Keep your toenails trim

- Extra boot laces are a must. It’s like having a spare tire in a car. If you blow a tire, you need to be able to change it and keep driving. 550 cord works well for this and serves other purposes

- When practicing your ruck marches, don’t just throw weights in your pack; carry practical items that you may need in an emergency such as food, medical gear, extra water, more socks, cell phone, poncho and a survival kit. Once you have those items in your pack, then add additional weight to meet the requirements you’re striving for

There are a number of tips and tricks not mentioned. Through time, you will find what works best for you and what doesn’t. Remember, a ruck march is a mode of travel from one point to another. Its purpose is no different than driving or flying in to accomplish a mission, once you arrive at the objective, you still have a job to do. Conditioning your body to get you to the object is the first step. If you’ve exhausted yourself to the point where you can’t perform your task, then your mission has failed.

Rucksack – noun: backpack a large bag, usually having two straps and a supporting frame, carried on the back and often used by climbers, campers, etc., [origin 1866, from Germany: Rucksack, from Alpine dialect Rück “the back” (from Germany. Rücken) + Sack “sack.”].

By MSgt Peter K. Bowden

Air National Guard Security Forces

12 MAY 2015

Airmen from Langley Air Force Base, Va., honor fallen defenders by marching through the streets of Amherst, Va., during the Security Forces 9/11 Ruck March to Remember Aug. 25, 2011. Langley AFB Airmen traveled 141 of the 2,181 miles to pay their respects to the fallen defenders of Operation Enduring Freedom. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Racheal Watson/Released)